Artists exhibited

Also representing the works of

-

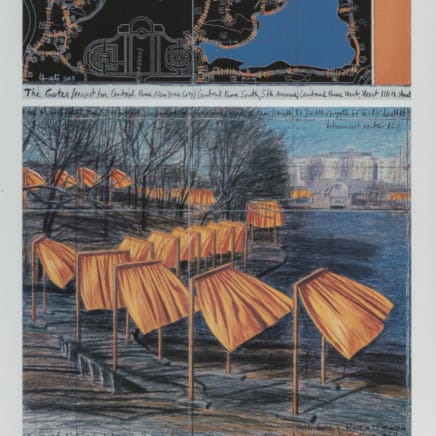

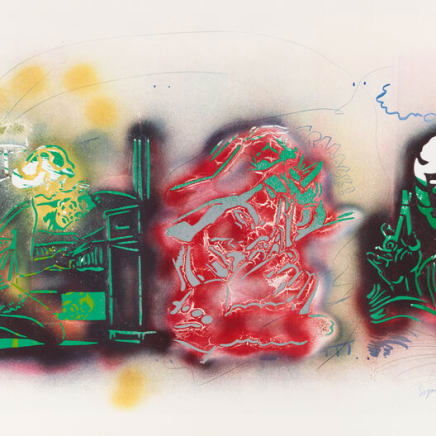

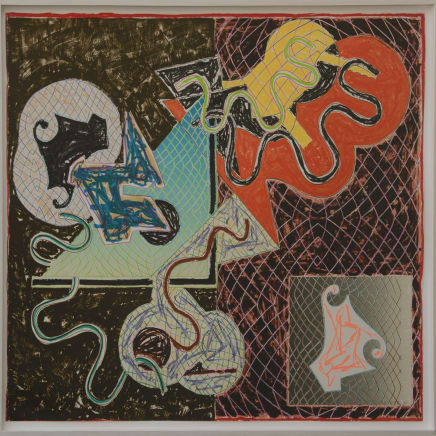

Christo

-

George Condo

-

David Hockney

-

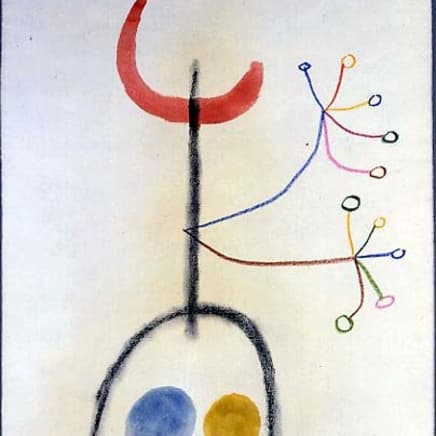

Joan Miró

-

Alejandro Monge

-

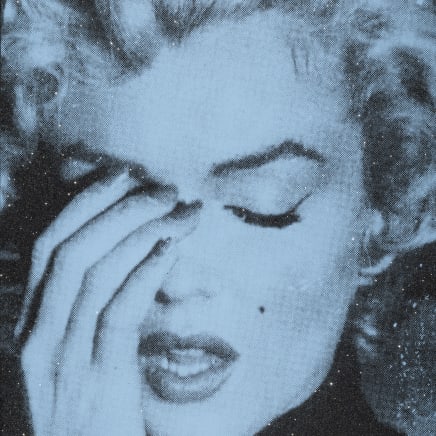

Sigmar Polke

-

Frank Stella

-

Massimo Vitali